Wizard Kings and Deep Time

By Todd Elliott

Akumal, Estado de Quintana Roo, México, Sunday, 13 October 2024 A.D.

Mayan Long Count Date: 13.0.11.17.15 Tzolkin: 2 Ix Haab: 17 Yax

Hello friends,

This will be the second and last of my dispatches from the Yucatan. We survived Hurricane Milton and it appears the Yucatan coast, where we were staying, was spared the worst from that record breaking storm, which at the last minute turned Northeast, leaving Florida, unfortunately, to bear the brunt of its wrath. My prayers go out to all who have been affected by both Helene and Milton. I don’t even have words to express the sorrow I feel on seeing the heartbreaking damage.

As we were preparing to leave the coast, where we were staying in what amounts a fortified house surrounded by a concrete wall and equipped with a generator, I was profoundly concerned for the people who lived in the nearby port city of Progreso, many of whom live in very inadequate shelter in low lying areas. Thankfully they and we were spared. We were lucky to be able to secure accommodations in the small Mayan village of Tixpehual, just outside the historic state capital of Merida, where we stayed for four nights in a modern house surrounded by jungle. Our first night there, while Milton raged outside with wind driven torrents of rain and the power flickered on and off, I was rudely awakened from my restless sleep by an uncanny grunting sound right outside the window. It took me a while to fall back asleep because it occurred to me that the sound may have been a prowling jaguar of which there are thousands in the Yucatan. As soon as I fell back asleep the creature returned and grunted insistently outside again. I realized I would never get any sleep with a large predator caterwauling outside my window so I decided to try to scare it away by yelling at it, which didn’t deter it until I told it to get lost in Spanish! It stayed away the rest of the night. I think it was more likely that the creature was an ocelot, a harmless, smaller feline common in that area. In hindsight I wish I could have seen it!

Using Tixpehaul as our base, after the danger of the hurricane had passed, my family ventured into the historic center of the old city of Merida, which was a major Mayan city, before it became a colonial capital. The following day we went to the ruins of the ancient Mayan city of Uxmal in the hilly Puuc region of the Yucatan, which unlike the rest of the Mayan sites in the state had to rely exclusively on rainwater for crop production. Most Mayan sites in Yucatan, then as now, are situated near water filled sinkholes which formed in the cracks in the karst limestone produced by the catastrophic impact of the Chicxulub meteor. These deep pools filled with clear cool water were essential to the growth of the Maya cities in the region.

Puuc sites like Uxmal, on the other hand, have no cenotes and were often dedicated to the cult of the rain god, Chaac, whose favor is necessary for crop production and whose image is prominently featured in relief sculpture there. Chaac is still very much venerated by the Yucatan Maya to this day, who petition him in a ceremony known as the Cha’a Chaac, to provide the rain necessary for the essential maize crop. We were able to see a tourist version of the ceremony nearby, which even though brief and performed on demand for tour groups, was nonetheless, a lovely and powerful ceremony.

The site of Uxmal is dominated by a large rounded pyramid known by the evocative name of Pyramid of the Magician, the construction of which is tied to the legend of a magical dwarf, the child of a witch, who bested the king of the city in a trial of strength and wits, building the pyramid overnight and becoming king himself as a result. Although I could find no links between the following lore and this site, I nevertheless found an intriguing article which asserts that the kings (and queens) of the Maya were in fact sorcerers who used magic to secure and maintain power against their rivals. Maybe the Pyramid of the Magician is an apt title after all!

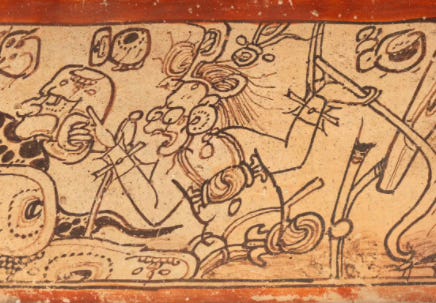

Folklore of modern Maya people as well as their Classical ancestors tells of mysterious spirits or demons known as wahyoob (singular wahy or way), nightmare beings who are the personifications of disease and misfortune and associated with witchcraft and sorcery. In a fascinating paper entitled “The Wahys of Witchcraft”, Mayanist David Stuart tells us, “the wahy beings were the embodiment of “dark” forces operating within Maya society and politics, wielded by rulers as a means of social and political control. Through their frequent depictions in painting and sculpture we can begin to see that sorcery was hardly an obscure and esoteric subject among ancient Maya elites, but was instead a key operating principle within the dynamics of political power, warfare, and state ideology.”

In Classical Mayan art the wahy beings are depicted as freakish, chimeric, and grotesque creatures, skeletal beings or unnatural beasts, or humans with bizarre features. They were associated with deities of Xibalba, the Mayan underworld. Historical Mayan documents and ethnographic reports among contemporary Maya peoples link the wahy with the personified spirits of diseases and with evil illness causing animate winds that can be manipulated by brujos and shamans alike for the purpose of causing harm to enemies. There is also a tradition of rulers being powerful sorcerers dating back to pre conquest times.

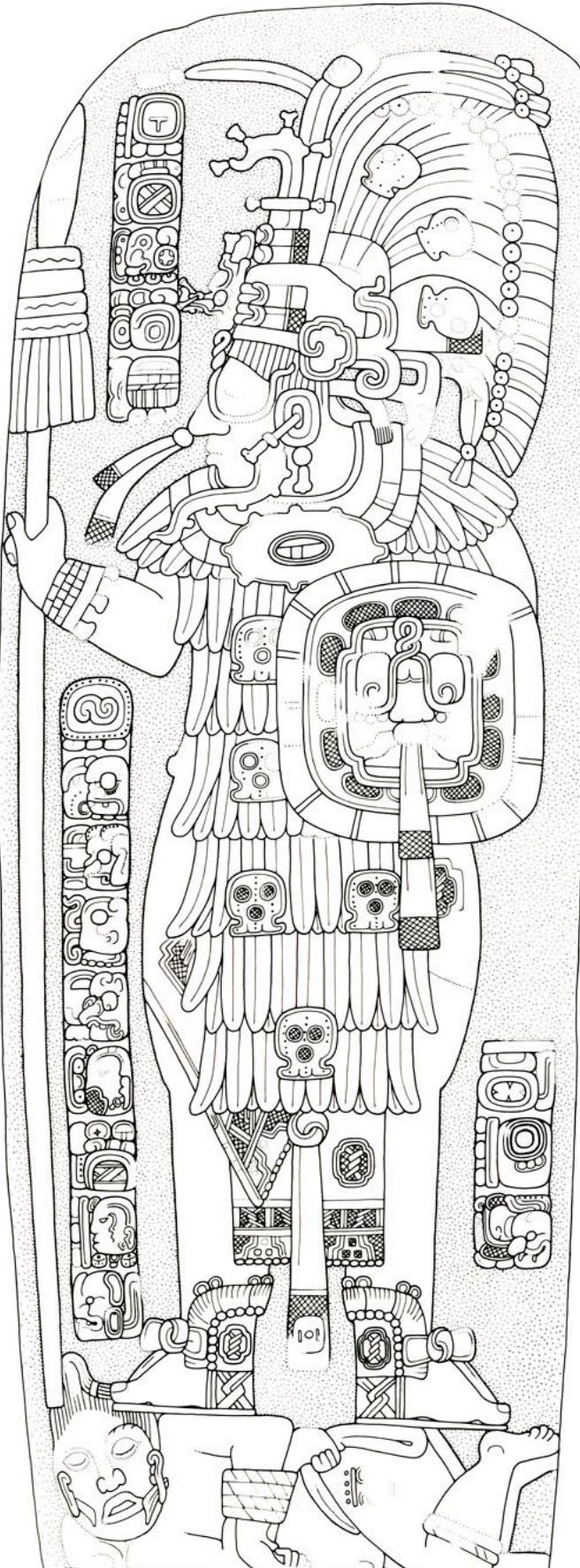

The concept of the wahy is somewhat similar to the concept in Western magic of the familiar spirit, a spirit helper or demon often taking grotesque or animal form, who helps the magician to carry out their will. Stuart believes that certain Mayan stelae depict victorious rulers wielding wahy beings to subdue their enemies and maintain coercive power. The ruler as sorcerer, the wizard king, summoning dark forces from atop a pyramid, or a dark cave, deep in the jungle, in order to sicken rivals or strike fear in the populace is certainly an evocative image, and one that was very much in my mind while I visited these powerful sites.

As our stay in the Merida area came to an end, we next drove west toward Tulum on the Carribean coast of the Yucatan, in the state of Quintana Roo, stopping on the way at the incredible lost city of Coba, home to one of the tallest pyramids in the Yucatan, Ixmoja, which rises from the jungle to a height of 148 feet. Unfortunately, we were unable to climb it because it was under construction at the time of our visit. Another incredible pyramid at the site is the Iglesia, meaning “the church” in Spanish, an imposing structure made all the more eerie by the vultures that were roosting there.

The beautiful grounds of the site feature the deep shade of tropical forest with enigmatic ruins in various states of repair and decay scattered throughout. One feature that especially interested me are the stelae depicting powerful Mayan queens and which also depict, according to mayanists, some of the largest numbers ever depicted in Mayan hieroglyphic numerals, depicting dates hundreds of millions or even billions of years in the past, conceptualizing times before the beginning of the known universe.

Before we continue, a brief digression regarding Mayan numerals and the calendar is in order:

Recall the date of this writing at the beginning of this post:

13 October, 2024 A.D.

Mayan Long Count Date: 13.0.11.17.15 Tzolkin: 2 Ix Haab: 17 Yax

The esoteric numbers above give temporal coordinates in two systems of time reckoning, namely the Western Christian Gregorian calendar and three time counts of the ancient Maya. The first, the so-called Long Count, counts the days in ever increasing cycles of time starting from a mythical day zero which is precisely, according to our calendar, 11 August, 3114 B.C. As with other calendar systems around the world it was necessary to have a day zero from which the count proceeds. The Jewish calendar, for example, starts at the mythical creation of the world, 3761 B.C. The Christian Gregorian dates we use on a daily basis also have a (no offense intended) mythical start date beginning with the birth of Jesus Christ. We don’t know why the Mayan calendar starts when it does, no reason is given in the surviving texts, but we can assume that it was a mythologically significant event.

Readers may remember the fuss about the supposed “end” of the Mayan calendar on 21 December, 2012. Actually, it was more like the rolling over of an odometer, than the end of the world, the Mayan date would have been 13.0.0.0.0 4 Ajaw 3 Kank’in, Ending a cycle of 13 Baktun, or periods of 144,000 days, or 5,125.366 solar years.

Without going into excessive detail here, the Long Count, using the basic unit of the day (Mayan kin) allows the calculation of very large periods of time without the error which creeps into lunar or solar calendars, which need constant correction. It uses ever increasing cycles (mostly, except for the second order, called the uinal, which has the value of 18) progressing in orders of twenty up to the largest named cycle, the alautun, (which we briefly discussed in a recent post) having the value of 23,040,000,000 days or 63,123,288 years.

Mayanist J. Eric Thompson summed up the Long Count neatly thus:

“These, then, are the periods of Maya time: the tun (a unit of 360 days), the katun (20 tuns), the baktun (400 tuns), the pictun (8ooo tuns), the calabtun (I6o,ooo tuns), the kinchiltun (3,2oo,ooo tuns), and the alautun (64,ooo,ooo tuns).”

There are also two other calendars which are used by the Maya, one a sacred 260 day calendar, the Tzolkin, composed of two interlinked cycles, one of 20 day-names, each of which has a hieroglyphic sign and is related to a god or a spirit, and concurrent with the day names are a cycle of number 1 to 13, which run together. Giving each day a number and a name, as well as a spiritual quality for divination or election of ritual times and other activities. It is similar in many ways to astrology, but is not related to the stars, although the Mayans were enthusiastic and skilled astronomers. The number and name combinations of the Tzolkin cycle don’t repeat until 52 years have passed when the return to the beginning of the cycle. This cycle of 52 years was extremely significant in Mesoamerican thought.

Another calendar is the Haab, a 360 day calendar with 5 intercalary days that is tied to the solar year. The Haab has 18 months of 20 days each, and each of the 20 days of the Haab has its own name. Because the whole Haab year is 365 days long, and the actual solar cycle is 365.25 days, and would fall behind 15 days in 60 years, a fact of which the Mayan calendar priests were well aware, another count, known as the secondary series was necessary in order to keep the Haab tied to the necessary events of the solar year, such as the timing of planting and the observation of solstices and equinoxes.

With this very brief sketch of a very complex subject in mind, we now have enough background to proceed to the importance of the inscriptions on Coba stelae 1 and 5, for readers who are unfamiliar with the topic. The Mayan calendar is a fascinating subject, and will be discussed in greater detail in my upcoming series of posts Cosmos and Chronos.

When we got to Coba, we decided not to avail ourselves of the services of one of the authorized guides who were waiting at the entrance to help visitors around the site, and explain the significance of the various buildings and inscriptions. Much as I would have enjoyed it, a two hour guided tour is just not something that is possible with small children and we never know exactly how long our youngest is going to hold up, especially in the tropical Sun. Or his dad, because it often falls on me to carry him!

The reader may recall me mentioning the stelae at Coba in my last post, but I hadn’t seen it at that point and only knew that they were somewhere at Coba, and that we intended to visit there in a few days time. Well, oddly enough in that whole vast site, actually several sites, scattered throughout the jungle, the inscriptions in question were in a corner of the site, far from the main attractions, the pyramids, but it was almost as if we were drawn to them. They were among the first ruins we came across, having made a wrong turn and walking right past the main attractions and down a side trail, Sacbe 9, to the group of ruins known as the Group Macanxoc, a group of smaller temples in the forest by a large lake.

The stelae I was seeking are fascinating not only because of the huge numbers which describe vast aeons of cosmic time, but they are also dedicated to the victorious reign of a Mayan queen, Lady K’aawil Ajaw, who ruled as the kaloomte of Coba from 642 and 682 A.D. and is depicted trampling on her conquered enemies. She was apparently so awesome and powerful of a ruler that her image is on a stela with the only known inscription of the largest number known in a Mayan inscription, a number many factors of twenty larger than the alautun.

Thompson, writing in 1950, tells us in his Mayan Hieroglyphic Writing:

“Only one example of the alautun and yet higher periods may exist. On Coba I there are a number of glyphs preceding the record of I3 kinchiltuns, and each of these has a coefficient of I3. It is possible that one or more of these represents higher periods in the vigesimal system. The glyph preceding I3 kinchiltuns appears to have the tun sign as its main element, and this is surmounted by an effaced prefix. It may well represent I3 alautuns. In passages dealing with reckonings of millions of years into the past at Quirigua there are a couple of glyphs which have the tun as their main element, and which may represent the alautun or even higher periods, but their identification must remain unsolved for the present.” (Thompson, 1950, p. 148.)

David Stuart, in his book on Mayan time reckoning, The Order of Days, refers to this vast chronological abstraction as the Grand Long Count. This is what it looks like in the long count notation used by Mayanist scholars to record dates:

13.13.13.13.13.13.13.13.13.13.13.13.13.13.13.13.13.13.13.13.0.0.0.04 Ahaw 8 Kumk’u

Without getting overly technical about the mathematics (it’s not my strong suit), each 13 at each place is multiplied by a power of 20, which is added to the next and which increases by one factor of 20 at each place. Got it? Me neither! But for us non mathematicians out there basically it boils down to a fantastically large count of days, which when divided by 365, is a still fantastically large number of years in the past: 28,285,978,483,664,581,446,157,328,238.631 years to be precise. (Stuart, D., The Order of Days, pp. 182-186) This figure is obviously many times greater than the age of the current universe arrived at by modern physicists, which is something on the order of 13,700,000,000 years, give or take 200,000,000 years or so.

What compelled the Mayan priests to engage in such lofty and abstruse computation? It seems like they had entered into a conceptual space where they could engage with deep time, pushing the boundaries of the infinite further back into the past. It is almost as if by making such vastness thinkable with their mathematical powers, they were able deepen their understanding and engage with time as an entity. Beyond the calendar gods of the day and the year, the rulers of the night and the planets, lurked the distant powers of the alautuns far out beyond the beginning of everything they knew. Even beyond anything we know. Thompson continues, “Later, with progress in astronomy and growing skill in computation, the Maya priests burst the bounds of the baktun, and roamed farther into the past: they probed with their calculations outermost time, as modern astronomers with giant telescopes penetrate to the recesses of the universe.”

There is so much enigma surrounding these astronomer/priests and wizard kings that we will likely never know exactly what they were up to. The lack of solid evidence has led to a great confusion of misinformation and fantasy about the Maya and I certainly don’t want to contribute to that. So I will explicitly state that this place, the Mayan world of the Yucatan and beyond, has definitely captured my imagination. And what follows is pure speculation.

I imagine that this engagement with the mathematics of deep time was a spiritual quest to go beyond the beginning in exalted states of mind. Perhaps these speculations were fueled by the entheogens the Maya were known to use. It is exactly the kind of thing you would expect from a mathematician on shrooms. Interestingly, this type of computation existed in the same cultural world as the craft of the wizard kings who summoned spiritual powers, the wahyoob, to maintain their grip on power and vanquish their enemies. The same people may even have worked with both the power magic and plumbed the depths of beginningless time. Or maybe they were separate disciplines. One can imagine a taboo that would prevent the priestly caste from engaging in the magic of statecraft, to keep them from becoming too powerful. Or perhaps, like the court vizier in the West, engaging in the magic necessary to the work of the state on behalf of the rulers, and pursuing the time work in their own studies. A clue, perhaps, is the presence of these vast numbers on the stelae glorifying the victorious conquest of the queen, thus associating her greatness with the vast infities of deep time, the work of an intellectual using his or her knowledge to flatter a patron.

Now we are staying at the lovely beach town of Akumal and today is our last day here in the Yucatan. I am grateful for both the rest, the inspiration, and the adventures my family and I have had. I am specifically thankful for the people we have met during our time here who have been kind, welcoming, and helpful. It has been an experience of a lifetime for all of us.